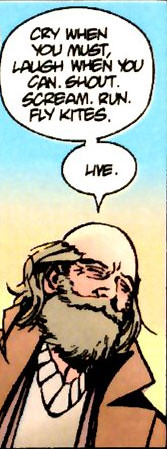

... and maybe the last lesson.

So often is it cited as a core truth of almost any practice (law, medicine, sports, magic, or life) that I feel almost shameful mentioning it here: It is always the simplest pieces that take the longest to master.

They are always taught first, and always take the longest to teach. When I hear the word "fundamentals" I cannot help but hear it in the gravely, heavily accented voice of my high school water polo coach. He yelled that word at least once a practice for all four years of school, usually followed by "god damn it!" He was not wrong to make this a near-mantra.

In this respect, Ekistomancy is no different. The simplest action within the practice is the most vital.

Be present with the city.

That's it.

Be present with the city.

You live in it. So do thousands or maybe millions of others. It is the amalgamated physical result of billions of man-hours of thought and dream and action. The least you can do is acknowledge its being around you.

The city is an arcology of buildings: examine them from basement to roof-beam.

The city is a mass of people: chronicle them as if you were a writer hunting for characters.

The city is a wunderkammer of objects: take them home with you, recombine them, and push them back out into the world.

The city creates the air you breath and the (usually) concrete ground under your feet: feel them.

Look around you. Notice. Record. Wonder. Enjoy.

Sunday, September 27, 2009

Wednesday, September 23, 2009

Possible Worldviews for the Practice [Ekistomancy]

One fact I take for granted across my whole practice: cities contain within them a fair bit of magic.

But where does this magic come from? From what place does it extend? Are there other paradigms for magic that fit living in cities?

Another thing I take for granted is the notion that magic uses some kind of energy system to work. That is to say, places that are "very magical" I understand to have large concentrations of some kind of etheric energy, while places that are "magically dead" seem to lack this energy (I use the word etheric not in an effort to create circular logic, but in an effort to avoid it. I use the term as shorthand for "unknown to science and also seemingly unmeasurable". Whether this is Reich's orgone or some other invisible energy is, to use a pun, immaterial). Now, it is entirely possible that this energy model is wrong, that magic is more like a field of forces, or maybe something entirely different, but having experienced things like clear magical flows, fountains, and sinks, I feel that an energy model is, if not correct, a half-decent approximation.

In any case, I would like to present a couple of different sources of the magical energy I find in cities, as well as some of the traditional methods for manipulation the energy that might flow from these sources. For any given ritual, I tend to find one or more of these possibilities applicable. Some of them are mutually exclusive, but I like to think that when held in the kind of dialectic framework post-modern magic is known for, even mutual exclusivity can be reconciled vis-a-vis appeals to shared base principles, etc.

Ley Lines

Out of all the possibilities presented, this is perhaps the most direct decedent of neo-pagan thought. Ley Lines, or Dragon Lines, or Lines of Power, are roughly, a system of energy lines embedded within the earth, across and around local geographic points. They are most well-recognized in England and Ireland, and in China under the geomantic rigors of Feng Shui, though practitioners contend that they exist across the whole earth, a kind of extended web of transmitted and received geological etheric energy.

Ley lines tend to be easily visible in rural land- animals follow them, so do brooks and rivers. Some contend that they are not magic at all, but a certain kind of mapping-thought-onto-land that seems to be universal among humans, less an actual property of land than a way of seeing it.

In a city like Pittsburgh, the Ley Line model makes perfect sense, as the city is old enough to have been laid out not on a strict and rigorous grid, but on the kinds of cow-paths and "flat but winding" road systems that tend to go along ley lines. When I try to seek out ley lines for use in my work, nine out of ten of them run right down the middle of arterial Pittsburgh streets. The other one-in-ten happens either in a city park that lacks streets, or at places where the street system seems to have interrupted itself due to considerations of grade, previous land ownership, etc.

On the other hand, when I lived in Los Angeles I found exactly two ley lines in the whole city- an intersection atop Signal Hill (in Long Beach), which also seemed to mark that spot as the heart or belly button of that city (more on that later). Everywhere else, the grid seemed to have overtaken and eliminated whatever ley lines may have naturally occurred there, driven it, to pardon yet another pun, underground.

Which leads us to our second model:

The Grid

So if the natural lay and curve of the land in a city doesn't seem to hold (magical) water, one might turn to the next clear system of movement- the street grid. This certainly has non-magical bearing on the character of a city. Manhattan wouldn't be Manhattan without its rigorous grid of Avenues and Streets, nor would Los Angeles be LA without its mile-by-mile parceling of land, and such rigor seems to foster some amount of magical energy.

I would contend, however, that strict geometric city grids do not so much foster an etheric energy that flows (like blood through a body, or rivers across land), but rather heightens magic's resting state, at least when it concerns very geometric functions. I tend to imagine a very computer-simulation-esque kind of grid, all glowing green line floating out and above a boring plain. Structured city grids, I think, tend to be a good base on which to build highly structured magical forms, but a terrible place to build magic that has any sense of motion or life beyond, say, the level of a computer or an equation.

Part of the nature of a grid is its very Cartesian normalness- it equalizes all places it touches, making them all, in some sense, the same. Where the power of this comes from is in the forcefulness of its imposition upon the ungrided land, the replacement of more "natural" structures with the severe logic of mathematics. The cities where the grid has displaced the lay of the land as the guiding structure for building are cities that in some sense have abstracted themselves away from notions of place or land. They are mighty institutions, sure, but their non-integration with local spirit and character deadens them somehow.

Again, I seem to have built a nice segue into the next topic:

Genius Loci: Organizing Spirits, Local Ghosts, and the Shadows of History

The word "genius" in Latin means, literally, spirit. Where our word for applicable intelligence comes from is the roman notion that artists were not themselves creative, but rather were channels for the creative power of these sort of muse-creatures that hung out near them. So to speak of someone's genius was to speak of the shadowy entity that was constantly throwing them ideas and visions. It was not to flatter them; in fact is almost belittled the artist's own creative thoughts, and rather praised his ability to translate forms from etheric to physical.

A Genius Loci, then, is a "local spirit", not in the sense of "ghosts tied to a certain place", but rather "the sense of place" itself- a sort of guard and edifier of a particular location, a preexisting force or creature that shapes a location into what we see of it physically.

Ley lines seem tied to characteristics of the land around them, but the causality of that association is unclear. So it is with Genius Loci.

Here are the thoughts of Alexander Pope, English Poet, on the subject (in verse, of course):

Consult the genius of the place in all;

That tells the waters or to rise, or fall;

Or helps th' ambitious hill the heav'ns to scale,

Or scoops in circling theatres the vale;

Calls in the country, catches opening glades,

Joins willing woods, and varies shades from shades,

Now breaks, or now directs, th' intending lines;

Paints as you plant, and, as you work, designs.

What draws a genius to a certain place is unclear- they seem, when they are discovered, to have always been there. A neat trick.

An aside: in gardening and landscape design, the notion of the grid and the idea of a sense of place are the two guiding principles of the field, and the proper meshing of their interactions the mark of a true master.

I give, for you, the example of Mount Vernon's gardens. George Washington had two gardens built next to the house- the upper, or northern garden, and the lower, or southern garden.

The upper was a vegetable garden, meant to supply the house with food year round. As such, it was (and is) a testament to regime and order; it is rows and grids, a neat, nearly phylumological series of plant-types, careful gradients of soil-types and the botanical rigor of a textbook graph.

The lower garden, on the other hand, was meant to be a wilderness- to show plants not in neat rows but in natural clumpings, an artfully designed mini-paradise, bringing the wilderness right up to the foundation, but taming it as well, so that if one was to sit, one could look out and see the whole of the natural world unfolding and exposing itself like some delicate crystal.

The point, though, is that one garden was not whole without the other: Mount Vernon, and George Washington, needed both.

And so it is with urban spaces. As much as city magic is imposed by the grid of streets, the flows of people and traffic across the city-scape, it is also informed by the very specific, unique sense of place that different spots in the city engender.

Overlooks and vista points are wonderful places to work communication magic, as the very character of the place fosters the casting of a wide net, the spectacle and vision of looking out from the highest hill or the tallest tree.

Freeway underpasses, to take the opposite example, are a great gatherer of detritus and secrets, and an excellent place to work magic that requires things to be tossed aside, buried, and generally put underground. They are huge bridges, underwhich hide mighty trolls.

Some senses of place, though, come not from spirits far more ancient than man, but from the very human history of a place. Signal Hill, in Long Beach, CA, for example, might be such a magical spot because it is the highest (and really, only) hill for miles, but it was also the site of the first oil spout in town, the place where the city first had a reason-to-be.

These origin-places are sometimes called omphalae (singular omphalos), Greek for "navel", a literal center. Indeed, the usually-cited "omphalos" is the Greek one, just near Delphi, which is said to have been located by two eagles Zeus sent out to find it. Some legends say that they found not a navel, but the largest earth spirit ever seen, the Python for which the prophetic pythia, the Oracle at Delphi, is named. Apollo himself is said to have tamed it, and buried beneath a great rock, also called the omphalos.

In any case, more modern omphalae have much more human origins- they represent the seats of civilization in particular areas, the beginnings of settlement.

Other nexuses, not exactly omphalic but certainly central, might be formed through conflict or violence, or from the long shadows of historical action. It is these non-central locations whose sense-of-place might not draw from metaphysical spirits, but from real ones- ghosts and shadows of past human action. A site of great slaughter, an old market square, or the place where some great figure died, might all gather mystical forces about them pertinant to those past injuries or experiences.

Though some omphalos are simply central places, many of them really do seem to have a larger, central genius to them, one that perhaps is the emperor or organizer of its greater locality.

There is another school of thought derived from this hierarchical theory, the idea that perhaps whole cities are organized not by the mass collection of local spirits in the area, but by

The Living, Deified Heart of the City Itself

Or, as some might think of it, the metaphysical instantiation of the city as a centralized being, whose wants and wishes are reflected in the greater function and geography of the city.

Under this rubric, the city itself is a kind of localized god or deity. Different cities would be ruled by different gods, whether by the god gathering the city around it, or by a good adopting a settlement as a kind of patronage. The most direct and well known example of this later phenomenon is Athens, Greece, whose patron deity is, of course, Athena.

In my own case, I believe that Pittsburgh, the god, not the city, was formed much more recently, beginning during the first human habitation as a sort of organizing idea, and growing to incorporate in its own will and whim the desires and drives of the humans who settled (or conquered) the area, evolving its divinity organically with the population, but with a larger eye towards the future.

As such, these City-Gods are the rulers of their stated domains, and have a feudal or at least governmental relationship to the smaller spirits and forces under them. But that idea of hierarchy points to a further thought:

The All-City; The Ur-City

Perhaps there is not a separate god for Baltimore and one for Brooklyn. Perhaps, instead, there is just one god, the God of Cities generally. Perhaps the cities of the world are each facets of one archetypal city, the sort of city on a hill that near-mythical Golden Age Rome is supposed to have been.

Perhaps, though, there is a City Court, presided over by the most ancient of archetypes, with the cities of the world arranged in their respective standings, vying for a piece of the population pie. Maybe there is no central authority, just a loose brotherhood or pantheon of city gods.

Or maybe there are no gods per-say, just one great Platonic City, capital C, whose etheric shadow looms large over our physical dimension, instantiating itself repeatedly across our world, tying civilization to itself in one great Gordian knot of streets and cars and skyscrapers.

Conclusion

Or maybe all these things are true. Maybe the unseen realms from which magic emanates are just crammed to the brim with all sorts of idea-forms and godlings, smack full of ghosts and geniuses and gods, lousy with loci.

Maybe when tapping the street-power of some traffic artery to enforce some spell upon an area one is really calling the aid and attention of a genius loci, or maybe one is through supplication influencing the will of the unitary Great City, or maybe one is simply enforcing human will onto the local geomantic ley lines.

In the end, why ekistomancy works is less important than that it works at all.

In my own practice, I use whatever belief from the above set seems most appropriate and handy. They are all situationally valid, and in a way, they might all be the same thing- tools of thought.

Labels:

ekistomancy,

tools

Monday, September 21, 2009

Tools of the Trade [Ekistomancy]

So how does one go about this Urban Magic business, exactly? Like man modern practices, ekistomancy asks its practitioners to craft certain tools for ritual and magical use.

The living-in-your-parents-house response is usually "but what if I don't have access to these kinds of things? What if my parents find my stash of magical rail spikes? Why can't I use astral tools, so that no one has to know?"

Well, sure, you can use astral tools instead of physical ones. I've done magic with both, and let me tell you, actually holding something magical that you've found, fashioned, and/or built in your hand, feeling the weight and temperature of it, is orders of magnitude easier to use as a tool than building some kind of astral dagger or what-have-you. As much as the city one wishes to interact with may exist in other, stranger realms, it is in large part a physical place, and appreciates physical tools.

That said, in another sense, it is only in those further, stranger realms that this tool actually holds any kind of might or power, and so it is just as good to hold in your mind the thought that superimposed onto whatever physical tool you craft is an astral/etheric/urbanomantic double, the importance of which should not be done away with.

Development

When I first started practicing ekistomancy, it was while also attending the Golden Triangle Temple, run by my good friend S. Knight. Temple 31, as it is also called, descends from a long line of western mysticism that traces itself through the six-kinds-of-awesome occultist Tau Allen Greenfield, through the organization he schismed from, the Ordo Templi Orientis, back through the Order of the Golden Dawn and back to the early Christian Gnostics.

But since the closer end of this line of mystical succession is actually a series of heretics and demi-heretics who have acquired legitimacy from their once-sects, but moved on to start newer, more interesting ones, Temple 31 draws from more recent and strange circles (Chaos Magic, Pop Magic, Post-Modern Magic) as well as more Crowley-ish trappings.

As part of Temple 31's weekly Magic Roundtables, some of the more Chaos Magic inclined of Temple 31's members began down the path of magical tool creation and subsequent use laid out in the ill-named LIBER KAOS KERAUNOS KYBERNETOS, or Liber KKK (The author, Peter J. Carroll, is British, and as such has no associations with that particular three letter acronym).

The rather short book lays out the general framework for a long term magical practice, a framework that can really be applied to almost any system.

Imagine, if you will, a 5x5 grid.

The columns are the classical magical acts: Evocation, Divination, Enchantment, Invocation and Illumination.

The rows, from Top (hardest) to Bottom (easiest) are:

High Magic

Astral Magic

Ritual Magic

Shamanic Magic

Sorcery

What Carroll suggests is that the beginning magician work his way up from the bottom, perfecting all five acts for each level before moving on to the next one.

He goes on to specifically define the first fifteen operations (Sorcery 1-5, Shamanic Magic 6-10, Ritual Magic 11-15). Astral Magic is a revamping of the first three, but entirely within the mind, and as such is sketchily defined.

Carroll finishes by pointing out that by the time one reaches High Magic, "The magician must rely on the momentum of his work in sorcery, shamanism, ritual and astral magics to carry him into the domain of high magic where he evolves his own tricks and empty handed techniques for spontaneously liberating the chaotic creativity within."

For Temple 31, those of us participating endeavored to complete the first rung- Sorcery. Further rungs were planned, but interest moved around and along, and at least in that context we never got to them as a group, though we continue on our own paths.

In any case, from this Liber KKK workshop through Temple 31, I began crafting some of the tools I now consider essential and basic to any practicing Urban Mage. As tools they no longer quite match the exact specifics laid out in Carroll's work, but so it goes. The studious among my readers should feel free to analyze where my tools differ.

The Goods

This, my gentle readers, is the Key to Pittsburgh. It was constructed from, if I recall, a speaker knob, some kind of drawer handle, and, most importantly and awesomely, a beetle encased in a clear plastic marble. There are other Keys to Pittsburgh that other local occultists hold, but this one is mine. It is held in the hand, either knifelike or keylike, and used in those ways in ritual- cutting the air, opening hidden locks, turning spigots and spouts of magical energy across the city's ley lines. It is also kept in the pocket, a constant reminder of my intention and will as a magician.

In practice, the Key is used in almost every ritual I perform, as an opener-of-the-way, as a spiritual sword or instrument, as a way to turn energies on and off, or direct them in certain manners.

Before creating the Key during Temple 31, I tended to use rail spikes as my mode-of-cutting-and-opening-and-pinning. They are excellent for their weight and for their association both with movement (as part of rail systems) and their stillness (they are, after all, solid steel or iron). They are especially potent for use in Pittsburgh, as Steel and Iron were its founding industries, and rail one of its chief exports.

I still use rail spikes in my practice, channel and anchor ley lines, to construct guardians, to demark local sites of magical interest, etc. Anything that needs to be marked out or held down in a permanent (but reversible) way is treated to a healthy dose of spike.

This device-creature is a companion to the Key, a mostly passive drawer-down-of-information, a Library-Fetish, a little servant that aids me in finding and collating data on various subjects, that pulls secrets towards itself.

In practice, this Library-fetish is used quite passively. It sits on my desk and is willed at every once in a while to aid in a task. More than anything, it serves as a sort of research-time battery, lending back the help and strength I push onto it in less hectic times.

Mapping is a super-important piece of my practice, and as a 21st century mage, I tend to most of it on the computer. The image above is actually a cut from a PDF map put out by the Pennsylvania Mine Subsidence Insurance Board showing which parts of the city are at risk of, I am not kidding, abruptly being eaten by the earth.

I tend to use derives or drifts as my method of divination, rather than some specific tarot deck or rune set, relying on the whole city to show me the signs I need to see.

Some mundane materials play parts as well: a leather messenger bag, a notebook for recording signs/grafiti, a digital camera, and, sometimes, a stick of chalk, for putting up temporary sigils.

These tools are all part of a longer process, and in time I may move on to different ones. For now, though, these are what I use.

There are some more complicated magical constructions I have made, but I'll save those for another post.

Labels:

basics,

ekistomancy,

tools

A Survey of the Printed Fiction of the Field To Date [Ekistomancy]

Urban Magic as a field seems to be prefigured by quite a lot of printed fiction, specifically the horror genre and what is called the "New Weird".

Much of this fiction stems from the odd stories of turn-of-the-century American author H.P. Lovecraft. From his New England home, he drew strange inspiration from the new-but-ancient American landscape, and wrote many sordid tales of mankind's encounters with what became known as the Cthulhu Mythos- ancient alien beings of unimaginable power and imperceivable will, whose very forms could drive men mad. Many of his shorter works explored in some detail various disturbing elements of Greater Boston, especially the warrens and tunnels beneath Beacon Hill (Pickman's Model is the best example of this), though nearly all of his stories relied on the cities of the eastern seaboard as places under threat, or from whence threat might emerge.

Generally, Lovecraft moved the "horror" genre away from more rural tales, and towards the monstrous horrors of modern civilization and modern science. His "cyclopian, primordial cities" buried deep in the arctic or high in the Himalayas lend their vast strangeness to the steel canyons of New York, London, and Tokyo. His terror, as he once eloquently put it, was in the thought that one day "modern civilization" might finally link together enough strange facts that some greater, mind-destroying truth might be revealed. From the opening of his most famous story, The Call of Cthulhu,

The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

Many of the authors discussed below cite him as a direct or indirect inspiration for their work.

Post-Lovecraft

The most direct fictional use of urban magic, in the sense of magic or supernatural activities for and about cities, rather than in them, comes from Fritz Leiber's Our Lady of Darkness, published 1977.

Leiber, inspired by Lovecraft, started writing Science Fiction and Fantasy in the early 40s, and kept writing up until his death in the early 1990s. Our Lady of Darkness was written in the middle of his career, and breaks from his other work by being set in the present day. It tells the story of a (vaguely autobiographical) recovering, alcoholic writer, who from his San Francisco apartment discovers a strange and horrible magic about his city, with the aid of a strange volume of occult science called Megapolisomancy: A New Science of Cities.

In a very Lovecraftian turn, this volume is referred to as being a real, factual book, and its purported author, Thibaut de Castries, to be a real historical figure, and possibly Like Lovecraft's Necronomicon, Megapolisomancy is meant to be real. The author encourages citing it in other works, and there are those who really do look for copies of it. Our Lady of Darkness also introduces de Castries' second work, also fictional, a companion volume called the Grand Cipher or Fifty-Book, wherein de Castries explains the mathematics behind how magical forces gather in and around cities, what he calls "Neo-Pythagorean metageometry", as well as 50 key astrological figures and their uses.

Megapolisomancy deals very specifically with spirits called paramentals, elemental spirits drawn to cities by their dense collection of Steel, Electricity, Paper, and other "city-stuff". By arranging the very street grid, and by constructing skyscrapers of sufficient height, material, and design, one can apparently alter the flow of these paramental forces, and in doing so change the future. Obtusely, paramental seems to be both an adjective describing certain magical forces, but also a noun, describing the golem-like creatures.

The main character of the book, though, is not a practicing megapolisomancer, but rather a sort of hapless victim of megapolisomantic machinations.

Further googling of the term "megapolisomancy" revealed a greek wordpress blog, which used to contain a few articles, but now seems to be empty/abandoned, save for an ominous picture of the sky over a city. Strangely, one of these deleted articles was translated version of David Langford's short story BLIT, in which the author (and also editor of Ansible) first posited the idea of a basilisk, a specific image that "crashes the human mind", as well as defenses against them.

Spiral Jacobs, New Crobizon and UnLondon

New Crobuzon is the city in which much of the fiction by China Meiville takes place. The city was first introduced in his novel Perdido Street Station, where it was the lively backdrop for a sort of extended science-noir romp. The second book, The Scar, is mostly set outside the city, but it returns as a setting in the third book, Iron Council.

New Crobuzon is a vast, London-like city, inhabited by literally hundreds of humanoid and nonhumanoid races- walking cactus-men, bulky warrior hedgehogs, women with the heads of beetles, and disgustingly decadent frog-people, just to describe a few, which during the books is just coming out of an industrialization period, where objects are just as likely to be powered by steam engines as by steam elementals, and many fields of magic are regarded as much closer to science, or art.

Where these books intersect City Magic is in the character of Spiral Jacobs, seem most prominently in the third book, Iron Council. He appears for most of the book to be a crazy homeless man, endlessly wandering the city, and scrawling on its walls intricate, elaborate spirals.

As it turns out, the spirals are actually a linked series of strange sigils, placed at seemingly random, but actually hyper-specific locations around the town, and when they are complete, are used to turn the city itself into a living, breathing weapon against its inhabitants, and Jacobs (perhaps named for the great urbanist Jane Jacobs) not a mad derelict, but one of the most powerful sorcerers in the world.

Meiville's other books are more directly tied to city magic, mostly because they are set in the present-day. They are not fantasy, rather "Magical Realism" or "Urban Fantasy".

King Rat explores, if not a sort of magical London, than certainly an underground one, mixing the mid-90s drum-and-bass scene of warehouse raves and underground clubs with the Pied Piper of Hamelin and the cryptozoological urban legend of Rat Kings- groups of rats whose tails have become intertwined, acting as horrifying collective-animal-groups. It is definitely a work of Urban Fantasy, though like Our Lady of Darkness, no characters perform actual city magic, rather they experience magic or supernatural pheonomenon in an urban context.

Un Lun Dun, Meiville's latest, is most applicable to the field. It is a young-adult book describing the adventures of two young girls as they make their way through London's strange, magical twin city, UnLondon, a city inhabited by the cast-offs and leavings of its "normal" twin, presided over by an evil cloud of living pollution called, appropriately, "the Smog". Various magicians from both cities aid the girls as they battle the evil pollution cloud.

Neil Gaiman

Many critics have noted the similarities between Un Lun Dun and another recent book, Neverwhere, by Neil Gaiman. Neverwhere also tells of a normal person caught in a sort of sinister-twin-London, this one called London Below, this time a young businessman, rather than two young girls. After rescuing a young girl who turns out to be a sort of princess, but also a key-mage with the power to unlock any door, the businessman is drawn into the other-London, and must right certain wrongs before he can return to London Above. Some amount of city magic is performed, but like Un Lun Dun, the book mainly concerns a cast of strange creatures and characters inspired by and reflecting more concrete aspects of the city, such as The Angel Islington, an actual celestial creature, purportedly for whom both the neighborhood Islington and its Metro station, Angel Station, are named.

Other works by Gaiman have similar Urban Fantasy bents, especially American Gods, a novel which forwards the notion that the hundreds of years of immigration to America has brought to this country all of the old-world gods, or strange instantiations of them, as well as created new gods reflecting American wants and desires, such as Media, Celebrity, and Technology. Again, there is much magic in and around cities, but very little City Magic. Though at one point, the main characters do escape a city by traveling one of its strange, alternate alley-streets, which is very Paper-Street-esque (more on Paper Streets in a future post), and that probably counts.

At two other points does Gaiman play with cities. Both of these appear as mini-stories in the long comic Sandman.

The first, collected in Sandman Volume Three: Fables and Reflections, is called "Ramadan". The Caliph of Baghdad calls Morpheus, Lord of Dream, to ask a deal of him. The Caliph is troubled that Baghdad, in all of its glory, is impermanent, and wishes the Lord of Dream to preserve it. Morpheus preserves this Golden Age of Baghdad by sealing the magical, flying-carpet city inside a bottle, and recasting what are in fact real occurrences of magic as tales and legends, where they will live on forever. The Caliph awakens in a duller, sadder Baghdad, with no memory of its magical days save but in legend. This tale is told in a frame narrative to a young child in present day Baghdad, in whose thoughts the Golden City now lives on.

The second story is from the final volume of Sandman, a story called "A Tale of Two Cities", about a citydweller who awakens to find himself in a familiar-but-alien version of his own city, empty save for grey crowds of non-people. Slowly, he realizes that he is not in his own city, but in that city's dream of itself, the total unconscious-points of spectral geography that make up people's dreams about that city. Eventually, the man exits the Dream-City and wakes up, but wonders aloud what will happen when the City itself Awakens.

Gaiman later cited the Cthulhu Mythos as a direct influence over the second story: "You can tell it's Lovecraftian, because I use the word "cyclopean" in it."

This idea of a dream-city leads us to our next topic.

Invisible Cities, Unreal Cities

The lyrical, nearly poetic Italian author Italo Calvino wrote, late in his life, Invisible Cities, a book of prose poems, framed as a sort of scholarly debate about imagination and linguistics between Marco Polo and the aging Kublai Khan. As many merchants had done before him, Polo described to the emperor the various cities within his empire- brief, incredible descriptions of stories and experiences within those cities, half recollection, half dream.

In addition to capturing ideas about language, narrative, and imagination, Invisible Cities also captures the visionary potentialities that city structures present, their strange ability to foster all kinds of unreal structure.

TS Elliot's poem The Waste Land similarly ensnares and engenders this power of the cityscape to create, in the viewer, untapped mindscapes.

What is the city over the mountainsThe Subterranean and the Invisible

Cracks and reforms and bursts in the violet air

Falling towers

Jerusalem Athens Alexandria

Vienna London

Unreal

Both Neverwhere and Un Lun Dun, above, posited a sort of underground inverse-city, and that theme of subterranean habitation is continued in two other books.

The first is, like many of the above, directly tied to the Cthulhu Mythos, mixing Lovecraft with the rapid prose style of the Beat Generation. It is called Move Under Ground, by Nick Mamatas. It is a sort of sequel to the various autobiographical Beat books (On the Road, The Yage Letters, etc)- Jack Kerouac witnesses the ancient, terrible island-city of R'lyeh rise off the California Coast, and teams up with William S. Burroughs to drive across America and save the day. The entire book is available, free, here, for your reading pleasure.

City of Saints and Madmen, on the other hand, is pure fantasy, a series of connected short stories set in a strange city whose human inhabitants long ago pushed its founders, a race of mushroom people, underground, but, sinisterly, the mushroom people still live, and cast a long shadow upon the surface dwellers. Shriek: An Afterword is also set in the city of Ambergris, which the reader might note is named for the most secret and valuable excretion of whales.

And now, to round out the list we come to Grant Morrison's long-running comic epic, The Invisibles. In some ways, the work can be framed as a drug-addled occult-induced romp through every weird conspiracy and activity anyone ever thought up, having nothing to do with cities and city magic. But one would be overlooking the many subtle references and practices of city magic the hyper-allusive comic contains.

There are certain passages early on in the series that are clearly an aging ekistomancer, Tom O'Bedlam, trying to pass on his knowledge of city magic to Jack Frost, the main character. He shows Jack how to see the strange underside of Cities, how to meld with pigeon-minds, how to hide in plain sight, how to interpret graffiti. He speaks of ancient, alien, mushroom-like entities, whole planets taken over by this extraterrestrial notion of city-building, where the towers rise like gravestones over a dead population, as the cities have finally won out. He points out William Blake's Urizen, chained to the bottom of the Thames, and to the black pyramid atop the Canary Wharf building. He shows Frost the city as it truly is- alive and magical and strange, and most of all, able to be manipulated.

This magic, combined with the kind of strange spontaneous mixing of pop culture and ancient ritual that happens through the rest of the comic, is City Magic done right.

One of the key icons in the series, a sort of magical orb-satelite, is first seen as a graffiti scrawl in the London Subway, BARBELITH, which is now also the name of a very active web forum devoted to the topics that The Invisibles collated, including city magic. But that is the start of a whole other survey, which I shall save for another day.

Labels:

ekistomancy,

survey

Sunday, September 20, 2009

The Beginning: A Time for Definitions [Ekistomancy]

What is Ekistomancy?

Ekistomancy is the art and science of city magic.

Definitions breed further definitions. What do I mean by city magic?

City Magic is a narrow term that refers not to any magic done in cities by an random pagan, but specifically to that magic which is done with or about the city. Worshiping a particular street, leaving offerings for ancient denizens long passed, or drifting through downtown looking for signs (both prophetic and terrestrial), are all wonderful examples of ekistomantic practice.

Ekistomancy has been known by many names: the urban fantasy book Our Lady of Darkness calls it Megapolisomancy, literally the "Divination/Magic of Big Cities." This name was misinterpreted in a recent io9 article about city magic in film and print, calling it Megalopolisomancy. The roleplaying-game-cum-magical-handbook Unknown Armies calls it Urbanomancy, a sort of odd mix of Latin-based English and a Greek suffix. The book of the same name calls it City Magick. More properly (though not strictly proper) it should be Urbomancy, and some call it by that name.

Ekistomancy (my own neologism, which might also be spelled Ekistimancy) is derived from the Greek term Ekistics, a word coined in 1942 by Konstantinos Apostolos Doxiadis, a famous Greek architect and town planner, from an old, old greek word (oekistis) meaning, roughly, "shaper of settlements," referring ambiguously towards the people who build houses in a settlement, the houses themselves, and the person who directed those colonists in the first place. Ekistics itself has been accused of fostering car cities, and of not truly being a science, as it is claimed. Ekistomancy spurns and drops those criticisms- it borrows the base-word, but not the politics.

But why call it Ekistomancy? Why not one of those other terms mentioned above?

To make it stand out from the other terms, mostly. City Magic is not some fictional science writ by a half-mad Ex-European-noble-on-the-run, nor is it the basis for somebody's RPG character mechanics. It is a real, legitimate practice, and as such deserves a fancy greek-root name.

But what is this website, Ekistomancy?

A blog dedicated to the exploration of the field of Urban Magic- its core practices, its fringe edges, its history and its future.

For me, the author, Ekistomancy (the website) is a challenge and a promise. My goal: I will update at least weekly, and hopefully much more than that. A frequency-of-posting any lower than that is a disservice to the field and to my own practice, and to you, the reader.

A note on terms: Above, I have used perhaps seven terms for "city magic", with various capitalization, in an effort to introduce the idea in as many forms as possible. From here on out, I will try to stick to either "city magic", "urban magic", and "ekistomancy", with capitalization dependent on how corny it comes off as. One thing I often detest in occult books is the use of capitalization and misspelling to reinforce magical terminology, eg. "Green Magick", "High Holy Day", "Book of Shadows". If I capitalize "city magic", it is because I am referring not to any particular instance of city magic, but rather to the field or topic of City Magic as a whole.

A further note: I tend to use quotation marks (") the way that computer scientists do, as explicit references to other texts. As such, I flout MLA guidelines by leaving my quotes' internal punctuation intact, and by putting external punctuation strictly outside my quotations.

Labels:

ekistomancy,

meta

Tuesday, September 1, 2009

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)