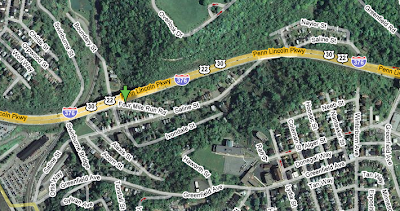

In the midst of Pittsburgh’s rolling hills Junction Hollow runs cardinally north from the Monongahela River past Schenley Park, petering out just east of Carnegie Mellon. The hollow is capped on this north end by the football field of a Catholic High School and the backsides of the shops on South Craig St. Two roads, Neville Street from the north and Boundary Street from the south, enter Junction Hollow, but end furtively half a mile from each other.

It was late in the afternoon one fall Saturday when I finished my jogging in Schenley Park. I had taken a path that meandered south across most of the park’s bridges, a path which ended abruptly near the East Parkway. In a clearing with a good view of the sun setting over downtown, I noticed for the first time that that the path did indeed continue past its marked end- the trail slid down a hill full of trees and scrub, across the train tracks that gave Junction Hollow its name, slid down and down to the train tracks and then Boundary Road.

I looked up at the sun- it was still well off the horizon- I had plenty of time to do a little exploring. I pulled my laces tight and set off down the hill. The scrub was much less aggressive than it appeared from above, and the descent went quickly. Before long I was at the tracks, two long iron snakes that fed north. I crouched and gripped one with my right hand- it was as still as a pond in early dawn. If there was a train coming, it was a long way off. I stood and made my way to the road.

It was darker here in the hollow, darker than I would have expected. I looked back at the hill, then south to the bridge that the Parkway made across the Hollow. Below it was the neighborhood without name. This moniker-less place was little more than a half dozen streets, all residential save for the large Orthodox church whose golden domes were a beautiful sight from I-376. When I was an undergrad at Pitt, a buddy and I had once contemplated buying or renting a house down here, but after meeting our potential neighbors, we decided it would be best to look elsewhere.

Its not that they were noisy or diseased or obvious criminals, nothing like that. They just didn’t seem… right. The father was a big man, bald, with bushy eyebrows like coal smears. I don’t remember much about his clothes or his body, but I do remember his hands- he shook mine- they were hard and knobbed, like bad roots, although unnaturally clean. His wife was the opposite- soft small, and dark, like a true Roma woman, a sort of genetic anachronism in a family that, so they proclaimed, had lived in America since Philadelphia was the capitol city. Their children, two boys of about ten, had the same darkness as their mother. Combined with their father’s eyebrows, there was something unsettling about their countenances, like they were embodiments of some ancient, grotesque portraiture.

The family, like their aging brick flat next to which we could have lived, had baroque lines, a heavy-handedness about their construction.

I shook this reminiscence form my mind, and looked again southward,, only to have my eyes rest squarely on those memory’s source- that ruddy, red house.

My entire vision of the neighborhood shifted then- I saw it as an English garden of the more modern style- the dozens of houses stood like flowers and bushes, specifically arranged to draw my attention away from the horizon down to this argillaceous house, a tiny behemoth of dusky brick in a neighborhood of blue and yellow paint, a white stone church, shiny steel bridges. Like the family it protected, the house was a throwback to the foreboding steppes of Eastern Europe, more suited to the Danube than the Monongahela, the biting cold of blizzards than the acrid smoke of steel mills.

At this thought of cold, I shivered and again returned to the present. The darkness was coming faster than I would have thought. It was time to go home.

I turned north and began jogging up Boundary Street, towards the bike path that connected its terminus to that of Neville Street’s. In the distance I could see the top dozen floors of the Cathedral of Learning. Like most nights they were under spotlight. Quite suddenly, I was reminded of a signal fire on a distant cloudy peak. I kept jogging.

I stopped to catch my breath at the start of the bike path. In the twilight, I could dimly make out the lines of map of the hollow on the side of a covered display. Like the straining fingers of Adam and God, there were Neville and Boundary, the bike path a thin line, lightening like, between the two. There was something else, though- about a quarter mile up Neville, a branch westward that I had never noticed. On the map it was a thin line, like the bike path, that ran northwest towards West Oakland, where my apartment was. Paper Street, the little line was marked.

I started jogging again. The twilight was waning- I looked up and could see a few of the brighter stars. Home was a pleasant thought now- a warm shower and some pasta, maybe a little wine, and the news at 11. The paved path was welcome in this half-darkness, much safer than jogging Schenley’s muddy uncertainty.

I reached the end of the path just when I heard the first whistle blow. The sound, as if it were some ponderous beast’s mournful cry, echoed up the hollow as only a train whistle can. I imagined it’s production, the steam from the boilers rushing out of a thin, tilted slit like demons bursting out of Hell, screaming their freedom in low, gut-shaking howls that bounded along the valley’s walls like running stags might bound in a moonlit pine forest as the nomads hunted them.

These thoughts? Where do they come from? I laughed at myself. I had spent too much time pondering that red house in the Neighborhood without Name, too many idle fantasies of caressing that dark gypsy woman, of pulling her dress up to her hips and… no. That wasn’t why we refused the rental next door. There had been no lascivious fantasies on my part. It wasn’t… it wasn’t a good neighborhood. It was too remote, too lonesome. It would have been a hard house from which to run a social life, especially with the animal carcasses all stretched out across the lawn next door, staked to the ground like- NO! They were simply a different kind of family. There had been no adultery, no rituals of blood. We had simply gotten a, a feeling about the place, and that was enough. I lived in an apartment now, one I should be getting back to.

Paper Street- I was going to take Paper Street home. A shortcut. I started jogging again, towards the Cathedral. That tower was growing now- I could see most of its forty-three-story bulk. Almost home.

The whistle blew again just as I saw the sign for Paper Street on the left side of the road. In the darkness, for night had truly fallen now, I saw steps rising up from the side of the hollow. Ancient concrete clung to the hillside like the root of some great urban tree. Gnarled bushes and swollen oaks surrounded the stairs, forming Baroque arches above the steps. I crossed the street and ascended into the wooden tabernacle.

The darkness here was almost tangible, like a thick black cloak. The shadows were aggressive. I did not know whether it was the stairs or the encroaching walls of wood, but it was suddenly and alarmingly cold in that lightless tunnel. What had been a walking pace I quickly doubled- trotting up the stairs, sometimes two at a time.

I looked ahead- the staircase disappeared upward, a stone sword thrust into the belly of the forest. I stopped for a moment at a landing, looking back. Was it- no. No, my eyes were deceiving me- the stairs behind me couldn’t be dark red, or crumbling under their own weight. It must be a trick of the darkness- I had run up concrete stairs, not rough brick ones. There was no redness climbing towards me across the steps, like a clay cancer, like the feral red eyes of some primordial wolf.

I turned my back on this shade of Fenris and hastened skyward, although no sky was in sight.

It may have been my speed, but this new ascent proved painful- not uncommon was it that I slipped and scrapped a knee, or took a tangling branch in the face. And still, faster and faster, I rose.

A howl exploded from behind me, wild and dark. No- not a howl, but the train whistle, that boiling klaxon. It was close now, the train. It must be passing the Nameless Neighborhood now, only half a mile south down the tracks. Perhaps, I thought, I might glimpse its form upon the apex of my accent, down below me in the hollow, down in the red clay of the valley, in the belly of the beast.

My legs burned as I ran. I was taking the steps two, three at a time, without regard for form or decorum. I lurched, stumbled up the hillside. Once, back through the tangle of my arms and legs, I saw the redness again, a bright, thick blight upon my vision. More branches slapped my face, branches or stalks or roots I knew not. Even as I climbed it seemed that the forest around me grew tighter, the walls thicker with bows- or were they twisted roots- a slick tunnel of wood and stone and dirt.

When, at last, I looked ahead and saw a darkness not as bleak as the rest- the sky, the blessed sky. Only ten, twenty feet ahead, only a few steps. A blast then, loud enough to shake the staircase. Clods of dirt rained down from the verritous ceiling, sticking to the blood that smeared my skin. The train sounded so close now, as if it was only a few steps down, roaring at my heels. Back from the jaws of death, back from the mouth of hell…

The sound tore at me as I took those last few steps in one great bound. I burst, leapt from the staircase on to… what?

I had fallen sideways on to two parallel iron spears- train tracks? They shook against me like dying animals. My vision went red. I looked up, south, at the lupine visage of a great iron beast rushing towards me, its wheels spinning demonically, its otherworldly cry echoing through the night, the battle call of Shub-Niggurath, the howling of a thousand blackened young. Ia! Ia!

I thought of her eyes, the gypsy woman’s eyes, and then it came: low sounds of ripping flesh, red clay dust in the wind.